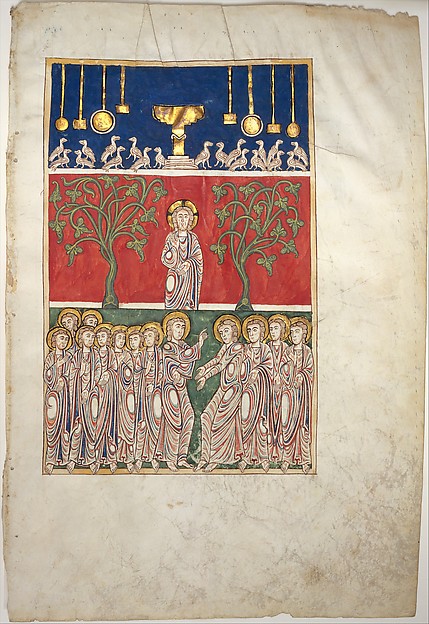

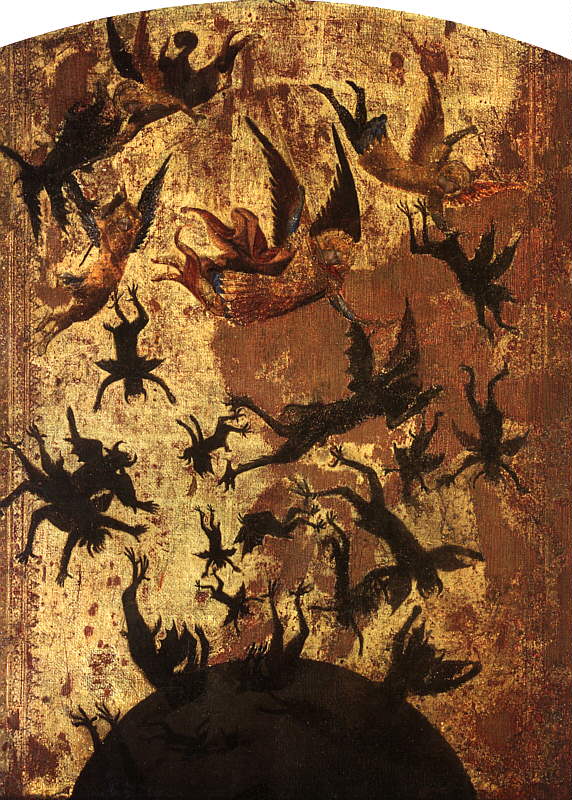

This work is a Spanish illumination made in 1180 in gold, tempura, and ink on parchment from the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was disassembled from the original book binding in 1870 and the Met acquired it in 1991. It is a leaf from a Beatus manuscript, a type of illuminated book unique to medieval Spain.

Leaf from a Beatus Manuscript: the Opening of the Fifth Seal; (1180), Spanish, from the Met collections

There are thirty two surviving Beatus manuscripts that depict the extraordinary vision of Saint John of the end of the world, as he recorded in the Apocalypse (the Book of Revelation). The Beatus manuscripts record the commentaries of Beatus of Liébana on this mystical vision of Saint John. The upper register of this leaf depicts an altar with suspended votive offerings, and doves symbolizing the souls of the dead. The middle register depicts Christ, and bellow him a group of figures in white are collected, gesturing emphatically. This illustration is based on the text of Revelations 6.9-11: “I saw under the altar the souls of them that were slain for the word of God…and white robes were given to every one of them…” Therefore the lowest register is a depiction of the Christian martyrs, saints, in their white robes.

The New International Bible translates the saints of the fifth seal as calling “out in a loud voice, “How long, Sovereign Lord, holy and true, until you judge the inhabitants of the earth and avenge our blood?” Then each of them was given a white robe, and they were told to wait a little longer, until the full number of their fellow servants, their brothers and sisters, were killed just as they had been.” The fifth seal is fascinating because it tells us that martyrs are expected to be “under the altar” because, even in the time of Saint John, the bodies of martyrs were sacred. By the 1180’s the custom of including relics in an altar was practically a rule; the altar was a reliquary for all intents and purposes. It was a house for material sanctity. The entire body of a saint was sometimes interred under the altar, although the desire for relics usually dictated that saints bodies did not remain whole. But the idea that the body of the saint would be reconstituted during the end days of the world “under the altar” makes sense; the local of sanctity, the focus of veneration and devotion in Christian life, is on the altar (and sometimes on the cult image placed above it).

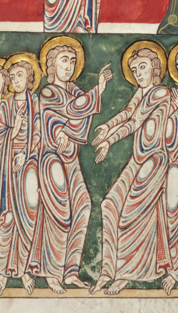

Detail of Leaf from a Beatus Manuscript: the Opening of the Fifth Seal; two figures gesturing among the martyrs.

This is a fascinating rendering of the opening of the fifth seal because it emphasizes communication. The martyrs gesture in such a way that they appear to speak; toward the center a figure throws their hands downward while another points upward toward the figure of Christ, but also toward the very top register with the altar and the votive offerings. These offerings are essential to earthly communication with the divine. Votives are given after a vow has been fulfilled; a crisis averted through the intercession and miraculous power of the divine channeled through a saint. The object of thanks is like the period in a sentence, physically signaling the end of a thought, the closing of a loop, a successful transaction. It is not the end of the conversation however, as it signals the devotee’s indebtedness to the saint and also represents their need to continue to venerate the divine figure.

Detail of Leaf from a Beatus Manuscript: the Opening of the Fifth Seal; showing hanging votives, the altar and chalice, and doves.

The indication of the objects above the martyrs; Christ, the altar, and the votives, is an indication of the votive exchange system. In life, the top altar, the devotee performs their faith before the altar and leaves votive offerings near it. The saints speak to Christ and perform miracles through Him. There are doves bellow the altar which represent the souls of the dead. They may be there to reinforce the notion of the martyrs under the altar, but they are also open to a different interpretation. Perhaps they are the souls of the faithful waiting to be killed; they are the future Christians that the martyrs in the Apocalypse wait for, the “full number of their fellow servants.”

This is certainly not the only interpretation of this image. However, it is a prominent one and one that would probably come to the mind of a medieval viewer with ease due to the predominance of the votive exchange in Christian culture. The altar is tiny in this illumination. It is topped by a large, central chalice which is directly above the head of Christ in the lower register. The background of this middle section is also essentially a red band. It is not spatial, rather, it creates a vibrant local for Christ and plays beautifully with the green of the two plants flanking him. But it may play another role in the reading of the manuscript’s image as well through the association of the chalice with the transubstantiation performed during the mass in which wine is converted through the priest into Jesus’s blood. Directly below the altar where this divine mystery takes place Jesus is shown silhouetted by a field of blood red. This re-emphasizes the tangible manifestation of the divine in physical matter. The transubstantiation of Jesus’s blood helps to justify the votive exchange; if the savior can become earthly, perhaps the gifts of a humble devotee can become manifest in the materials of the divine.

Detail from Leaf from a Beatus Manuscript: the Opening of the Fifth Seal; Chalice with Christ bellow.

To end, here is an exquisite game piece from the same period, but oceans away:

To end, here is an exquisite game piece from the same period, but oceans away: